Article published in Bilan, “Parlons cash” column, January 20, 2025, by Pierre Novello

Real interest rates are fundamentally determined by the level of inflation and the balance between capital supply and demand.

Influencing factors

If one closely follows financial news, it might seem that interest rates are essentially set by central banks, whose every monetary policy decision is scrutinized in relation to inflation control. But this conclusion is shortsighted, as explained by Michel Dominicé, partner at Dominicé Asset Management in Geneva: “Central banks cannot sustainably dictate the level of real interest rates—that is, nominal rates adjusted for inflation—because this level reflects the equilibrium between the desire to save and the willingness to invest. If they deviate too far from this balance, they will either cause a recession by being overly restrictive or trigger economic expansion leading to inflation. They are therefore quickly penalized if they ignore this principle.”

The real question is: where is this equilibrium point? According to traditional economic theory, real interest rates should always be positive, since delaying immediate consumption of one’s capital should be rewarded—that is, compensated. However, the evolution of market interest rates in recent decades suggests that this view no longer holds true.

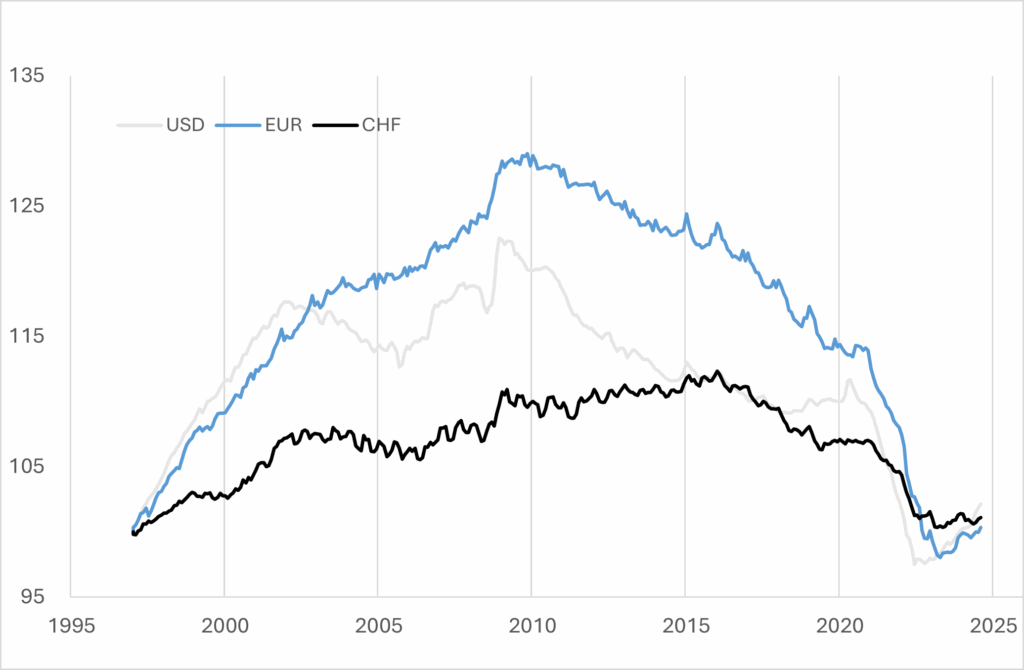

Over the past 25 years, real interest rates on the dollar, euro, and Swiss franc were positive during the first half of the period, but later turned negative.

Negative real rates

To illustrate, our interviewee prepared a chart showing the comparative evolution over 25 years, indexed to 100, of the real value of a three-month investment in dollars, euros, and Swiss francs. In other words, the investment’s value is inflation-adjusted in each currency. The chart reveals that real returns in each currency were positive until 2010, then turned negative—reflecting inflation rates higher than nominal interest rates, until the latter recovered only at the very end of the period.

This chart thus captures the shift that occurred after the subprime crisis of 2008, when central banks drastically cut interest rates—nearly to zero for the dollar and euro, and below zero for the Swiss franc.

“In theory, such an aggressive loosening of monetary policy should have triggered a surge in inflation due to the ballooning of central bank balance sheets. That expansion was further amplified by the Covid crisis, requiring the continuation of these policies. Ultimately, inflation did return, prompting monetary tightening, but this was due to the extensive supply chain disruptions caused by the pandemic.”

Knowledge economy

To explain the absence of inflation following ultra-accommodative central bank policies, our expert points to profound changes in monetary mechanisms, driven by two main factors:

“The first is related to information technology. Prices are under pressure due to increased transparency and the reduced risk of shortages. The second factor is a new equilibrium in real interest rates that has emerged over the past 15 years—one that is now negative.”

“Several elements justify this new balance between capital supply and demand,” our interviewee continues. “These include the increase in savings—driven in part by longer life expectancy and wealth concentration. Intangible assets—those that require little capital, such as client lists or specialized know-how—have gained importance. We’ve thus entered a knowledge economy dominated by services. Excess liquidity has failed to find sufficient investment opportunities to trigger the inflationary surge many anticipated.”

The return of negative rates?

Switzerland is no exception to this trend.

“This combination of low inflation and low real interest rates translates into persistently low nominal rates for the Swiss franc,” continues Michel Dominicé. “Pressure on Swiss franc interest rates is further increased by current account surpluses, which reflect excess domestic savings. In addition, the Swiss Confederation’s sound public finances and the SNB’s independence reinforce the franc’s role as a safe haven, justifying why nominal interest rates on the franc are consistently lower than those of the dollar or euro.”

Looking ahead, if inflation continues to subside in the coming years for the dollar and euro—bringing their interest rates closer to zero—what options would remain for the SNB?

“To manage its monetary policy, the SNB may no longer be able to intervene in foreign exchange markets to counter the franc’s likely appreciation, due to its already swollen balance sheet,” our expert estimates. “That balance sheet has become highly sensitive to exchange rate fluctuations, posing significant risk of losses. To avoid expanding it further, the SNB might have no choice but to reintroduce negative interest rates.”